An interesting piece of history was brought to my attention as I was watching golf’s US Open last Sunday. Saddled up in the comforting recline of my couch, I watched the commentators pay homage to an incident involving old time golfing legend Bobby Jones. 100 years ago, during the 1925 version of the Open, Jones accidentally touched his ball while lining up a shot, and despite nobody noticing, he owned up to his mistake. This cost him a stroke, and, as golf is a game of scoring in as few strokes as possible, the championship, but it cemented his reputation as one of sport’s good guys. Such a self sacrificing honourable act seems a foreign concept against the backdrop of a current golf major, with the millions in prize money and sponsorships at stake.

Such an act these days, might not even be universally lauded, you can imagine the derision from an assortment of comment section wannabe Machiavellians, who in today’s dog eat dog world would never do anything that could get in the way of them obtaining the almighty bag (that is if they ever exited their basements). That’s if such an act is even possible, with camera’s tracking every inch of the course. The whole thing got my mind wandering, staring longingly into the idyllic world of the past. Were times just simpler back then? Were people more honourable? Were comment sections more cordial? Naturally I needed to know more, and a well-timed ad break meant I could turn my focus from the golf of the larger screen to the rabbit holes of the smaller.

Bobby Jones had quite the resume. He won 13 major championships, including 4 US Opens and 3 British Opens, but his greatest legacy is a golf course he founded and co-designed later in his career: Augusta National, the permanent host of one of sports most prestigious and unique events: The Masters. He was one of the biggest names in all of sports at his peak, and was recognized everywhere he went. This is despite never becoming a professional golfer. He was an amateur, only playing part-time and making his living as a lawyer.

You read that right, he won 13 majors, and he made not a cent from any one of them. Amateurism is a seemingly ancient and obsolete practice in today’s sporting landscape. Now, the goal of any smart athlete is to monetize their success to the highest degree possible during the relatively short window of their career. This was not the case in Bobby Jones’ day, where professionalism certainly existed but was not always the norm. In fact, the relationship between athletes and remuneration is a long and complicated one.

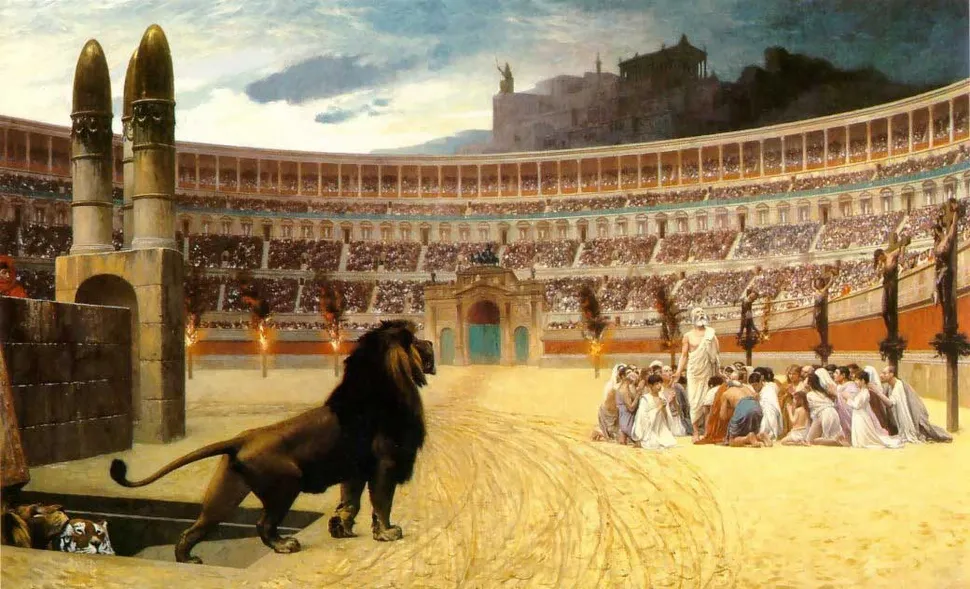

Let us go back to the Roman times, when the sports of the day included gladiatorial contests, watching criminals get mauled to death by various wild cats and horse-drawn chariot racing. In this anecdote we shall be focusing on the racing and not the poor condemned who became brutalized cat scratchers for the entertainment of the Colosseum going mob. Chariot races were a big deal, the Circus Maximus in Rome held an estimated 150,000 spectators and would be packed to the rafters on race day.

Gaius Appuleius Diocles is considered the greatest and most famous racer in Roman history. Across his 24 year career, he won over 2400 races combined in team and individual events. I did the math (an exceedingly simple calculation) and that averages to 100 race wins a year, that’s a lot of chariot racing! He earned a considerable sum of money from his exploits. Such a considerable sum in fact that, adjusting for inflation, and depending on which Greco-Roman historical source is your favourite, he is potentially the highest earner in sports history.

Despite Diolces’ substantial earnings and fame, he was a low class citizen in the Roman hierarchy. There is historical debate as to how much of his earnings he got to keep and what percentage went to his masters (like many Romans born from the wrong womb, he was likely a slave for at least a portion of his life). He started at the bottom, and despite his material wealth, his social status remained near the bottom, as competing for money in a sport was considered something of a disgrace to those in the upper echelons of Roman society.

Actors, butchers and prostitutes were among the other professions viewed in a similar light to chariot racing. They were performers, worthy of material reward, but seen as lesser contributors in a deeper sense. So while those in high places funded chariot races, enjoyed watching them, and even owned teams, they could not sit in the chariot themselves. This was one of the earliest accounts I can find of higher social classes looking down on those who needed to use sport to make a living, and while you can take two thousand year old historical record with something of a grain of salt, this is not an isolated phenomenon.

The Roman attitudes are in contrast to the riches and fame bestowed upon victors in the Ancient Greek Olympics several hundred years prior. Victory in the games would secure a mans status as a hero with riches lavished upon thee for the rest of his life (all of about 35 years on average in those days). The Ancient Greek games were staged several centuries earlier, and do not seem to have involved Lions or Tigers feasting upon the condemned. Societal change has not always moved in a linear direction. Despite the ancient Greeks lavishing riches upon their champions, the Modern Olympic Games on which they were based did not. They were founded in the late 1800’s as a strictly amateur event, with no professionals allowed to compete in the games until the 1970’s.

Jim Thorpe was one of the greats of the early Olympics, winning gold in both the Decathlon and Pentathlon at the 1912 games in Stockholm. Thorpe is in the conversation for one of the best all-around athletes of all time. In addition to his prowess in Track & Field, he played American Football to a high enough level to be inducted into the hall of fame at both the collegiate and professional level. He played several seasons of Major League Baseball, and played Basketball, Lacrosse and Ice Hockey to a semi-professional level. Some people are just born with it, aren’t they? Imagine being his high school rival, what would you do to get one over him? Take up dancing I suppose, oh wait, Thorpe also won a 1912 inter-collegiate ballroom dancing competition and I’m not making this up.

Controversy erupted several months after Thorpe’s Gold Medal wins, when it was found that he had played semi-professional baseball prior to the games thus breaking the strict rules regarding professionalism. The IOC barred anyone who made any money at all from sports, and their definition of a professional was expansive, extending even to PE teachers. He was stripped of his titles and had to hand his medals back for this grave wrongdoing. In reality it was very common for ‘amateur’ athletes to make money on the side playing various sports, Thorpe’s main mistake was using his own name while doing so rather than an alias. As always, it is not about he who does wrong, but about he who gets caught. Thorpe’s titles were eventually reinstated and his medals returned but not until 1983 which was, sadly, 30 years after his death.

Thorpe’s misfortune had a lot to do with timing. Many great Olympians became professionals after they competed at the Games, and this was absolutely fine. With a crafty strategy, a top notch athlete could remain amateur for just long enough to be eligible for the games, win, use the massive exposure to become a household name, then drop their amateur status and use the games as a platform for commercial success. One athlete did this better than anyone and you know that athlete today as Caitlyn Jenner.

Back in the 1970’s Caitlyn was Bruce and Bruce, like Jim Thorpe also competed in the Decathlon. Bruce played the game to perfection, dedicating his life to training 6-8 hours a day for the four years leading into the 1976 games in Montreal. He won the Decathlon with a world record points total and retired from competition immediately to cash in on his success (he apparently left all his pole vaulting equipment at the Montreal stadium, knowing he would never need it again). He then used his success as a springboard into the popular consciousness where became a beloved All-American Hero, and the face of Wheaties cereal. The endorsements and offers flowed. He entered into the world of celebrity and never looked back. Today Caitlyn Jenner has an estimated net worth of around US $100 million.

It was a struggle for Jenner and other American amateur athletes to compete at such a high level, especially considering that a lot of their main rivals were from the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union had their own strategy for dealing with the amateur issue: their athletes were not really amateur at all. On paper they held military or government jobs, but this was a front used to pay them for their sporting exploits. Nice for them, but it wasn’t all sunshine and roses. The pressure on Soviet athletes to perform was immense, and this pressure cost one young Soviet athlete dearly.

Elena Mukhina was born in 1960 in Moscow. She was a promising figure skater and gymnast in her youth, and like most elite Soviet athletes was found by scouts at a very young age. By the late 1970’s she was considered one of the best gymnasts in the USSR. She stormed onto the scene at the 1978 World Championships, defeating none other than the great Romanian Nadia Comaneci for the all-around title. The Olympic games were coming to Moscow in 1980, and she was expected to deliver the gold at home.

Despite already being the all-around champion, and arguably the best gymnast in the world, she faced pressure to add ever more complicated moves to her routine. The most difficult and dangerous of these moves was the ‘Thomas Salto’, named after the only gymnast to ever complete it, American man Kurt Thomas. The ‘Thomas Salto’ was a highly difficult move that involved a somersault into a forward roll landing, and due to the landing point being located around the upper back/neck area, there was no room for error. The move had never been completed by a female gymnast, but Mukhina’s coaching staff insisted she adopt the move into her routine.

In 1979 Mukhina suffered a broken leg during an event, and with the Olympics a year away, faced a race against time to heal and be ready. The pressure on her to be at the games heated up, she was rushed back from injury ahead of schedule and forced to complete a grueling weight loss regimen to cut the pounds she had gained during her recovery. With a severe lack of energy from her sudden weight loss, and a leg that was still not fully healed, she struggled to match her previous standards.

Everything came to a tragic head during a training session in July 1980, just two weeks before the games begun. While performing the ‘Thomas Salto’, Mukhina under-rotated her final somersault, landing directly on her chin. Her spine snapped and she was a quadriplegic for the rest of her life. Such was the pressure on her at the time, she later admitted to a feeling of relief that her paralysis would mean she no longer had to compete in the games.

In an interview following her paralysis, Mukhina made a scathing attack on the political systems of her country, her poignant interview with Ogonyok magazine showed the cracks that were appearing behind the iron curtain. She stated:

“…for our country, athletic successes and victories have always meant somewhat more than even simply the prestige of the nation. They embodied (and embody) the correctness of the political path we have chosen, the advantages of the system, and they are becoming a symbol of superiority. Hence the demand for victory – at any price. As for risk, well… We’ve always placed a high value on risk, and a human life was worth little in comparison with the prestige of the nation; we’ve been taught to believe this since childhood.”

The 1980 games ended up becoming a farce, with 66 countries, including the United States boycotting in protest of the USSR’s military invasion of Afghanistan, leaving most of the top athletes in the world at home. The USSR and the rest of the Eastern Bloc in turn boycotted the Los Angeles Olympics four years later, meaning it wasn’t until Seoul 1988 that the Olympics became a truly global sporting event again. Within a decade, the Berlin wall was to come tumbling down, just like all the Soviet institutions that helped build it. The Soviet sporting authorities for their part, did their best to cover up the details surrounding Mukhina’s injury, just as they covered up the fact that they paid all their ‘amateur’ Olympic athletes.

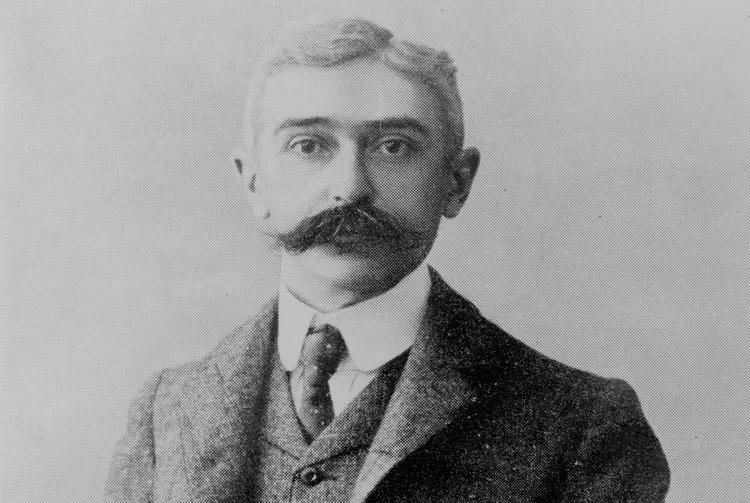

But why were the Olympic Games amateur in the first place? The games were founded by Pierre de Coubertin, a French aristocrat who’s passion for education had led him on a journey to Rugby school in England in the late 19th century. He admired the physical education program at the school and made it his life’s mission to implement a similar program across the French education system. He believed that widespread physical education would lead to a healthy and prosperous nation, and a stronger male populous that would be better equipped to win wars, such as the one his countrymen had lost to Otto van Bismarck and the Prussians in the 1870’s.

His efforts in his home country were unsuccessful, but not a man to be dissuaded by failure, he set his sights even wider to creating an international festival of sports based upon the Ancient Greek Olympic Games that he had learned about in his youth. He thought such a games would bring a massive benefit to the world, inspiring the masses to better themselves through athletic endevour, and inspiring people from all walks of life to come together for a common good.

His dream was realised with the staging of the first Olympic Games in 1896, and bar a couple of breaks for those pesky World Wars, the games have been held every four years since. Baron (yes, he was a Baron) de Coubertin was staunchly in favour of amateurism in sports and believed games should be enjoyed for their own sake, without payment to athletes, believing this would avoid the pure pursuit of athletic competition being taken over by commercial interests……….

Fast forward to the 2024 Olympics in Paris, and the games have long since disposed of this particular virtue in favour of the modern day virtues of viewership and sponsorship money. The previously amateur games now have a range of specially licensed McDonald’s burgers released every 4 years. It’s sickening really, however I will admit to being a little bit addicted to the McAussie in 2008 (essentially a quarter pounder with pineapple in a box with Olympic rings on it), it was commercial junk, it was crass but it was a good burger. 2008 was a golden Olympics, Michael Phelps and the Redeem Team were highlights, but nobody stole the show like Usain Bolt. I’ll never forget the feeling of watching Bolt win the 100 metre final with such ease, slowing down and thumping his chest at the finish and still smashing the world record. It was unbelievable to witness, and a reminder that sports at it’s best is pure emotional theatre.

The unofficial mascot of the 2024 games was Snoop Dogg, he kept popping up at every event. Watch the athletics, there’s Snoop in the crowd. Change the channel to the gymnastics, there he is again. This was Snoop’s true magnum opus, the completion of his transformation into an all-around family friendly good guy, past singles such as 213’s ‘My Dirty Ho’ now seem a distant memory. On a side note – remember when he called himself Snoop Lion for a time, and reckoned he was Bob Marley reincarnated? Not that there was anything necessarily wrong with that, it was just a bit odd and I feel like we all just collectively forgot about it.

Despite the feel good stories and the undeniable crispness of the product – modern Big Sport is extremely commercialized. It can all seem a bit depressing seeing the sports we loved as children becoming consumed by the machine, every inch of the proverbial flannel squeezed for every drop of precious profit. Every corner of the coverage decorated with ever more well placed advertisements and partnerships. Sports uniforms becoming billboards for brands that, aside from the direct credit payments, have nothing to do with them. 100 year old stadiums named after a community idol bulldozed, replaced by a cookie cutter stadium named for whoever wants it. Every avenue to generate income explored, implemented, exhausted and replaced by another avenue that generates more.

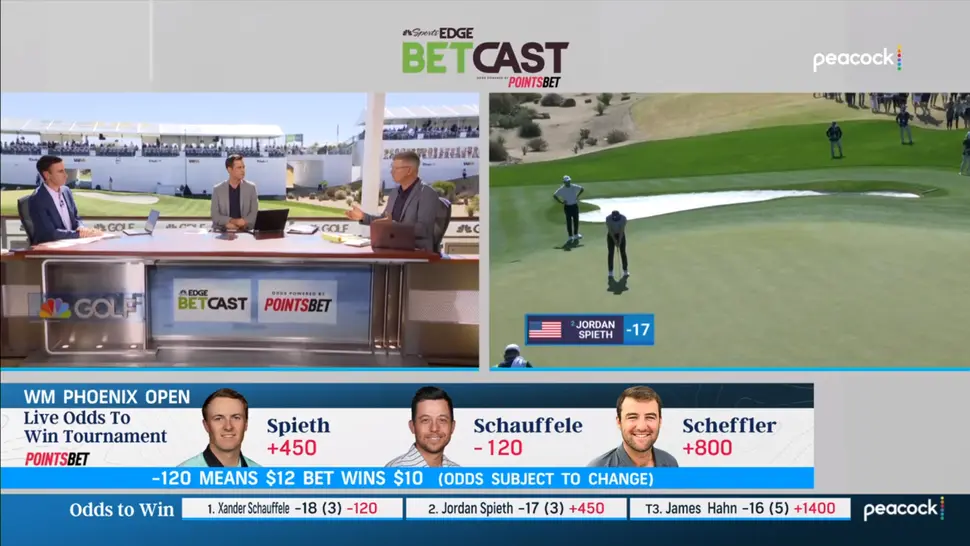

Even the viewing of sports has come to be increasingly monetized, with gambling at an all time high. According to statista.com, over 70 billion US dollars were wagered on sports in 2024 alone, with the majority of that fortune never returning to the pockets of the punters. People have wagered on sport since sport began, but for most of history it was done with at least some form of discretion. Now it is out in the open and almost completely normalized, odds displayed on the official broadcast of any given event. Few discussions about upcoming sporting events are devoid of further discussions about which odds might be good to put a wager on. The options are now limitless, with prop bets covering an ever expanding list of possibilities.

Add to this the ever growing obsession with data and analytics and the games we grew up watching can start to look unrecognizable. Yet another entity taken over by big money, and turned into another method to milk us like dystopian humanoid cows, longing for a past where we could feel something… anything. Back when jolly good sorts played ‘for the love of the game’ and were above such things as money and commercial interests. But this is only one viewpoint, and while looking at the past through rose tinted goggles is fun, it is still wise to occasionally take them off.

Let us zig-zag back to the late 1800’s, and Baron Pierre de Coubertin’s amateur ideals were certainly not unusual. It is interesting that he spent some of his formative years in England, where the divide between amateur and professional was for a long time a central pillar of the game of cricket. Cricket became a favourite past-time for the English gentry during the mid 17th century, when the political tensions of the time required much of the nobility to lay low at their lavish estates, where the expansive green fields were perfect for the game.

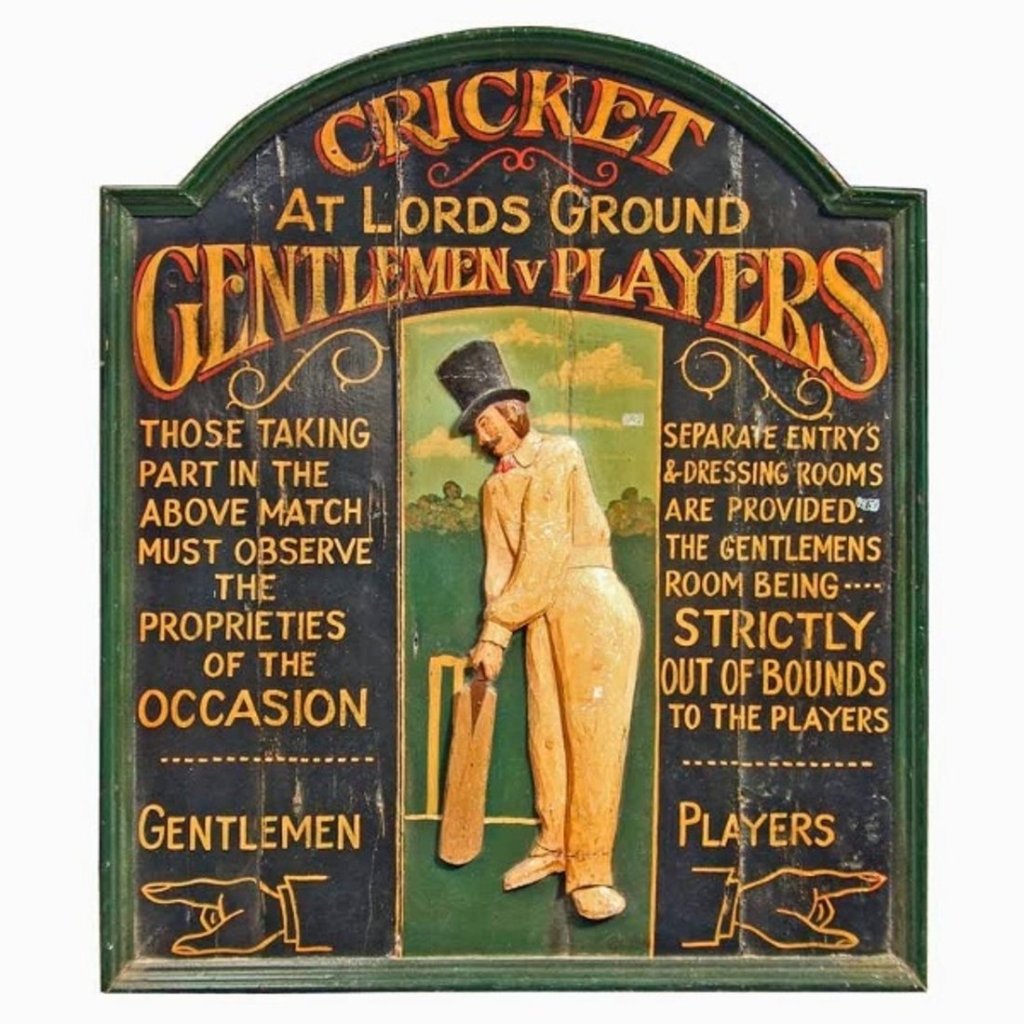

The political tensions eased up, but the gentry’s love for cricket did not and the sport’s popularity bloomed. Like much of English society in the centuries that followed, cricket was extremely classist and nowhere was this encapsulated better than in the prestigious Gentlemen vs Players match. The concept of the match begun in the early 19th century and was a highlight of the English cricketing calendar for over 150 years. It was essentially an all-star game between the best amateur and professional players in the land.

The class structure at play is clearly visible in the names of the teams – ‘Gentlemen’ and ‘Players’ – both words with underlying class connotations. The big difference between the two, of course was that the Player’s made money from their Cricket, whereas the Gentlemen played purely ‘for the love of the game’. Playing ‘for the love of the game’ was, of course, the more noble pursuit, but it is much easier to play ‘for love of the game’ when one inherited his fathers vast lands and holdings in Cheshire and much harder to play ‘for love of the game’ when one is born into poverty, but this was sadly the point of the entire distinction.

Amateurs (Gentlemen) were the ruling class, the old money. Professionals (Players) were the working class, the new (or no) money. While the amateurs were not openly hostile toward the professionals, they did consider themselves a cut above and this wasn’t just an unwritten rule. They used separate changing rooms on matchdays, were in sole charge of any amendments to the laws of the game, and held an almost total monopoly on leadership positions at all levels of the game.

What the gentlemen were not above however, was winning games, and outside of the annual amateur v professional fixture, most teams had a mix of both. Interestingly the divide crept into the on-field roles of the players. Most bowlers were professional, and most batsmen were amateur. Despite their obvious use, the stigma associated with being a professional was strong, and that stigma was even felt by one of the all time greats of the game.

Wally Hammond, was one of the great English batsmen. Ranked ninth in ESPN’s ‘Legend’s of Cricket’ series, Hammond was also considered one of the greatest catchers in the history of the game and one of the most ‘elegant’ players to watch. But, despite his immense talents, Hammond’s career and life were filled with inadequacy and sadness. His father was tragically killed fighting in the Great War in 1918, and after a promising early start to his cricketing career he suffered an extreme bought of syphilis (he was reportedly as prolific off the field as he was on it) that almost killed him and put him out of cricket for the entire 1926 season.

He eventually recovered, however the treatment of the time involved mercury. Overexposure to mercury may have led to him developing something of an aloof and moody persona, and he was disliked, even hated by many of his peers. Once he exploded onto the international stage, he enjoyed about a year or two of supremacy before the emergence of a man who he would spend the rest of his career chasing: the great Australian batsman Don Bradman.

Bradman’s test match batting average of 99.94 runs per innings is one of the most incredible statistical outliers in sporting history, no-one before or since has even come close to that mark, it is a remarkable number that takes a good knowledge of sports to fully grasp. For comparison, Hammond’s batting average was an incredible 58.4, good enough for eighth all time (*among batsmen that have played 40 test match innings or more), but a full 41 runs short of Bradman. Hammond was a great batsman, but Bradman was the best and Wally’s inability to match the exploits of the Don consumed him, anything he could do the Don could do better. Hammond was elite, he was elegant to watch, he produced all time great numbers for his country, but for the rest of his career he was never better than second best.

It was off the field however, where the chip on Hammond’s shoulder was the biggest. He was a professional, and felt the social hierarchy deeply. To try and bridge the gap and fit in with the upper classes, he spent much of his time off the field racking up unsustainable debts to keep up an appearance of a man well above his own financial station. While he made money from the game, it was never enough, and like Bradman’s batting, the Gentlemen of the day were always that little bit better than him.

Hammond did eventually attain amateur status late in his career, in 1938 he was offered a position on the board of directors of a tyre company, meaning he no longer had to rely on the money he made from playing the game. He was finally made captain of England, but the inadequacy from his earlier years never left him. Following World War II, many class and social barriers in England were surmounted. Len Hutton became the first professional captain of England in 1952. Ten years later saw the last edition of the Gentlemen vs Players, the players winning on the back of professional bowler Trueman. The victory was sweet for Trueman, who was outspoken in his belief that amateurism should be abolished. It was, only a few months later.

Amateurism at it’s essence, was a nice ideal, but it’s implementation in reality was more complex. As you look closer into the history of amateurism, you can see that those who championed it, and therefore those who did not become professional, were those who COULD. It came to be a status symbol, one used by those born into wealth and status to see themselves as better than those who needed to monetize their athletic prowess. Pierre de Coubertin himself was born into a wealthy French aristocratic family, and while his passion was undeniable and his views were noble, it is hard to separate them from the privileges his circumstances allowed him.

Add to that the various ways in which individuals and organizations circumvented the rules of amateurism, and it’s apparent that what was a nice ideal became a complete sham. From American athletes in the early 20th century playing professional sports under an alias, to the state sponsored tomfoolery of the Soviets, amateurism in practice was an illusion. Sports in the modern age has its issues, but whether we look back, forward or sideways, any era has its pros and cons, and a poison must always be picked. Sure, corporate interests and our zero sum society continue to turn our beloved sporting events and teams into cash cows, but at least there’s no class based changing rooms.

When those rose tinted goggles are removed, everything seems a bit less idyllic. Which brings us back to the man who started this whole rant, Bobby Jones. The sportsman, the good guy, the peoples hero. Remember the guy who did that wonderful thing on the golf course. Bobby Jones had a pristine public image, the curation of which lasts to this very day. Due to this careful curation, there are few stories of Jones being a racist man, but a brief look at the golf course he created gives us some clues. Augusta National was founded in 1932, and for much of it’s existence had a clear race-based class structure in place. Players were white, and the caddies who carried their clubs were black. It resisted the changing tides bought about by the civil rights movement long after the death of segregation. The first black member was not admitted until 1990, just 7 years prior to Tiger Wood’s sensational debut Masters victory. But Bobby Jones was one of sports good guys… rose tinted goggles indeed.

After all that reminiscing, I was ready to return to my modern day reality. I was now satisfied from all my armchair research that things aren’t so bad after all. Our era has its imperfections, but so did every other era, and to be honest I’d take the imperfections of mine. No more segregation, no more shamateurism, and the coverage is indeed so, so crispy. Enough reminiscing, let’s enjoy today, besides I had the golf on, time to put my phone down and watch…….. another ad break. Dang.

Fantastic read. Had a good few chuckles along the way

LikeLike

Seeing as I am not as knowledgeable about sports, I learnt a lot from this article. Really enjoyed dipping into the past and being able to acknowledge some key sportsmen and Olympians. Especially enjoyed the jokes. Damn McDonalds.

LikeLike